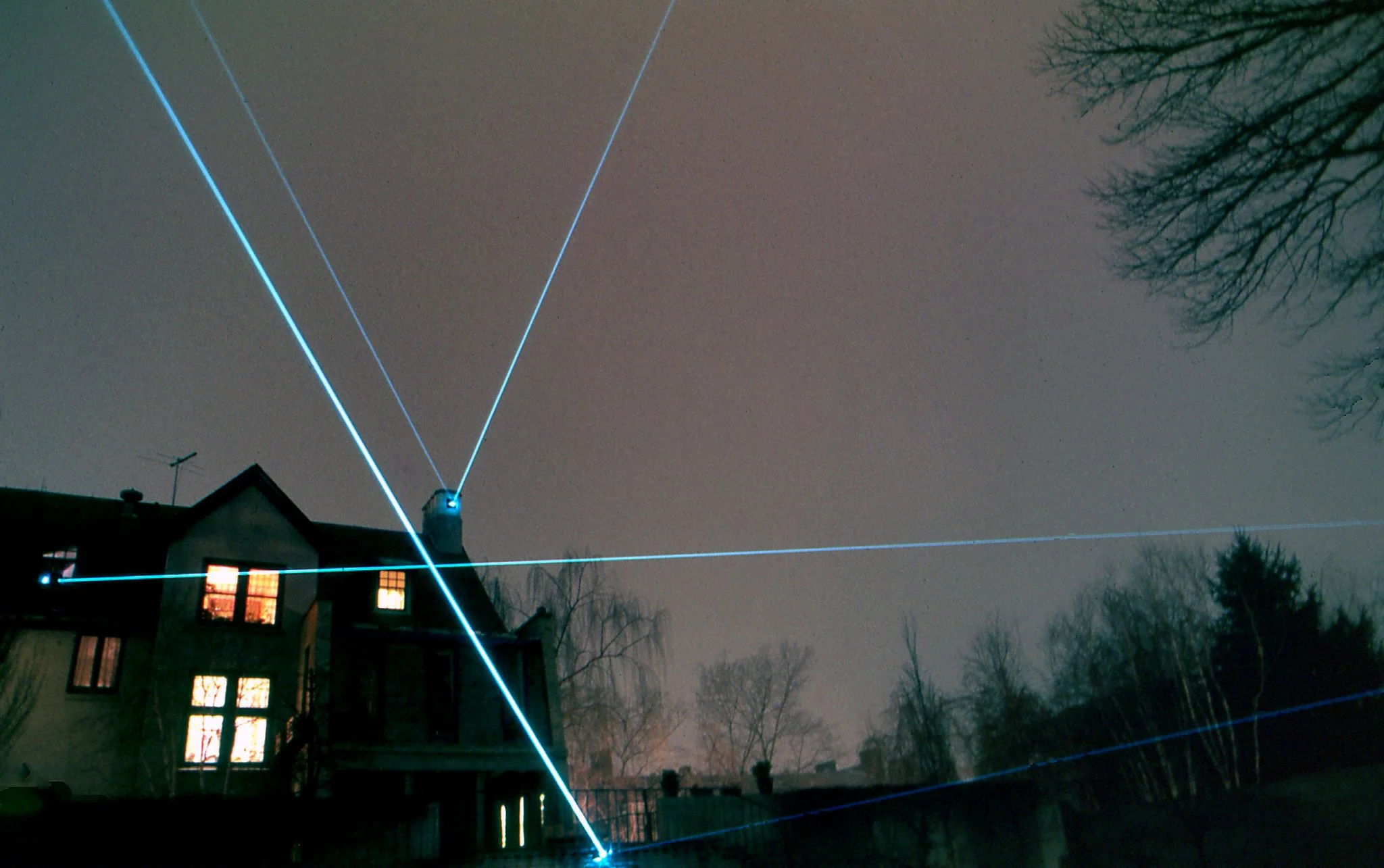

Urban-Scale Laser Sculptures

I think of these as pieces which you experience in total but see only in sequence or passages. The experience is a remembered experience, almost as a piece of music of which you hear the progression. In this case, you see the progression of the piece and your final total experience is one of memory. Rockne Krebs, 1970

The Sixth National Sculpture Conference, 1970, catalogue, National Sculpture Center, the University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS. Edited by Elden C. Tefft, published 1971. Published transcript of Krebs’ lecture.

Rockne Krebs principally sculpts with light, though he has worked in a variety of media. His objective is to define space and mark time. Though some hardware is always necessary to his sculpture, the work itself consists only of light. The light generally takes two forms, one natural, the other technological. Working with the existing landscape, he transforms it, playing the variability of light conditions against a formally rigorous system of mirrors and laser lights. This creates structures which appear solid and stable, but are actually immaterial and subject to atmospheric conditions.

James Earl Reid, Sculpture Today/Traditional and Non-Traditional, exhibition catalogue, 1980, The Art Gallery, University of Maryland, College Park, MD.

Rockne Krebs is one of the few sculptors working today to who the complex challenges of city life and city scale are both comprehensible and conquerable. Benjamin Forgey, The Washington Star, 1974

Rockne had that ability, to hold people spellbound. I remember him at a sculptors’ conference in Huntsville, Alabama, he was just remarkable.

Making those lasers come to life through 35mm slides and the power of his conviction.

William Dunlap, 2013

Krebs didn’t reject the premises of abstraction at all. In fact, his temporary environmental disruptions can be easily defended as forms of conjecture about the ultimate place of abstraction in modern life.... Because Rockne Krebs never saw a pressing need to qualify the role of technology in the process of artistic innovation, his ideas communicate with the absolute clarity and conviction of someone who envisioned our future as a place where the only limits to the sublime come from the failure of our imaginations to visualize it as reality. Dan Cameron, The Ghost in the Machine, The Technological Sublime: Works by Three Artists, Pazo Fine Art, 2022

“I found myself thinking of an evening in 1973, in balmier weather, when I walked from my apartment a few blocks from the Art Museum to see another temporary installation there, Sky Bridge Green by Rockne Krebs.

It consisted of a green laser beam shot from the Art Museum to a mirror atop City Hall and bounced several times across the Parkway. The atmosphere was like a party. People kept throwing objects to see if they could make this monumental beam of light disappear for a split second.

It was so much fun seeing the amazing light and the community it created, I went back for several more evenings to see it again and again.

The Krebs piece dramatized the polarities of the Parkway — with one end in the heart of the city with its commerce and politics, the other at the Art Museum, representing aesthetic contemplation and the gateway to a natural world beyond. On the ground, the Parkway often falls short, but Krebs’ work shined a new kind of light on the ideals that brought it into being.” Thomas Hine, The Philadelphia Inquirer, January 24, 2019

“I was working at the Philadelphia Museum of Art back in 1973,

when David Katzive, the head of the Museum's Division of Education and the Urban Outreach Program, commissioned Sky Bridge Green, which was one of the most extraordinary, beautiful artworks I have ever experienced. I watched Rockne tinker with the impressively huge laser that he had set up on the east portico of the Museum to shoot a beam of light straight down the Benjamin Franklin Parkway to a mirror on Billy Penn's hat on the top of City Hall.”

William F. Stapp, 2012

Former Curator of Photography, The National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC / Former Staff Lecturer Education Department, The Philadelphia Museum of Art

“THAT “Sky-Pi” (later changed to Sky Bridge Green) should really be called “Calder Green.” Never mind its given name or nonname. Just think of it as a laser beam environment…The laser lights will be greenish in color and here’s where the Calder Green comes in, says Krebs. He sees his piece as linking three generations of works by the Calder family: the Alexander Calder mobile in the museum; the Alexander Stirling Calder Swann Memorial Fountain in Logan Square; the Alexander Milne Calder statue of Billy Penn atop of City Hall…”Using a laser beam is just a way of making sculpture,” says Krebs, 34, whose 19 other laser environments have been shown nationwide. The laser is a tool, not unlike a pencil. The light from the laser is constituted so you can direct it to get linear drawings in space. “It’s an unusual 20th Century kind of structural drawing,” says Krebs, who points to historical precedents – such as Naum Gabo’s Cathedral of Light – of using light as the structure for art.” Nessa Forman, Art Editor, The Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, Laser ‘Sky-Pi’ Will Light Up Parkway Tonight, May 11, 1973

“Of the 38 major pieces I’ve made

in the last 10 years, two still exist.”

‘Rockne Krebs is recognized as one of Washington’s finest artists. Krebs “Of the 38 major pieces I’ve made in the last 10 years, two still exist. Perhaps I ought to start making still-lifes of flowers.”’

Paul Richard, The Washington Post, Making It as An Artist, 1977

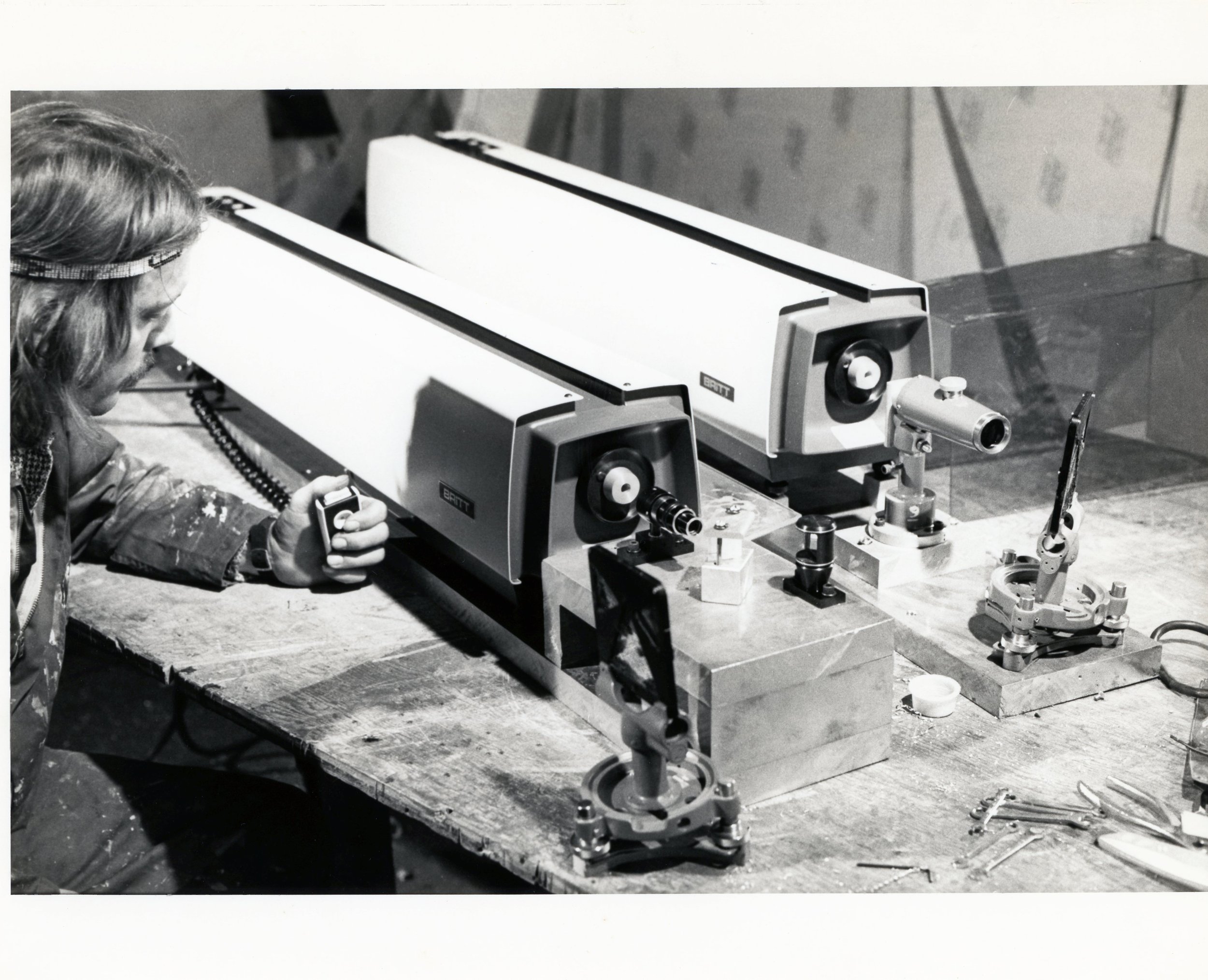

In the studio preparing for his 1971 solo exhibition at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, NY, curated by James N. Wood.